Neutrino Oscillations |

|

Neutrino Oscillations |

|

What makes KamLAND an important experiment is it's ability to detect "neutrino oscillations". Feel free to skip to the bottom of this page where we explain why neutrinos oscillations are important if you can't wait to find out, but for now we'll start by explaining what they are.

|

Although there are three distinct "flavors" of neutrinos (νe,

νμ, and ντ), in general, a neutrino

can be any mixture of these. For example, you could

have a neutrino that is 1/2 νe and 1/2 νμ.

This means that if you tried to measure what flavor the neutrino is,

half of the time you would find that it is νe, and the

other half of the time you would find it to be νμ.

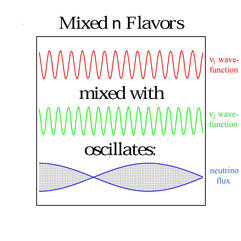

If neutrinos have mass, then there are three neutrino states ν1, ν2, and ν3 with distinct masses m1, m2, and m3. Each of these neutrino mass-states can be expressed as a mixture of the three usual neutrino flavors. So for example, ν1 could be a mixture of νe and νμ as depicted in the picture here. |

|

|

Likewise, νe could be expressed as a mixture of ν1, ν2, and ν3. So for example, if νe was a mixture of 1/3 of each mass-state, and you tried to measure its mass, you would get m1 1/3 of the time, m2 1/3 of the time, and m3 the rest of the time. Actually, our research aims to do just this, to measure these three masses, as well as find the fractions of time we get each mass for a particular neutrino flavor (we call these fractions "mixing parameters"). |

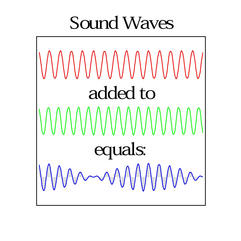

| Up to now, we have always referred to neutrinos as "particles". But according to quantum mechanics, particles sometimes behave like waves (and vice versa). When neutrinos "mix" as described above, they combine in the same way that waves combine. When sound waves combine, they "beat", as depicted in the picture to the right. Neutrinos do a similar sort of thing, except we say that they "oscillate". |  |

|

|

It is the flavor of the neutrino that oscillates. If a neutrino starts out as 100% νe, as it moves along its "νe-ness" will begin to fade, while its νμ-ness or ντ-ness grows. The νe-ness soon reaches a minimum, and begins to increase again. Then the neutrino once again becomes a pure νe before fading away again. This oscillation is depicted in the picture. The amplitude and frequency of the oscillation depends on the particular values of the three masses and the mixing parameters. |

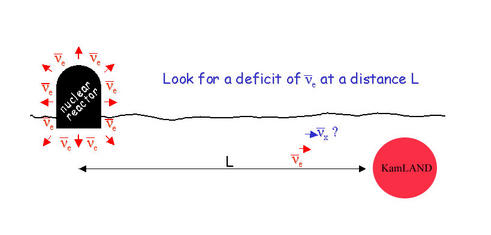

In KamLAND, we are looking for electron-antineutrinos ( s ) that are emitted

from nuclear reactors. If they are oscillating, then by the time they

reach the detector, they might be at a point in their oscillation cycle

at which they are not 100% s ) that are emitted

from nuclear reactors. If they are oscillating, then by the time they

reach the detector, they might be at a point in their oscillation cycle

at which they are not 100%  . This increases

the chances that the particle will pass straight through KamLAND

undetected. Thus, the oscillation

manifests as a "disappearance" or "deficit" of . This increases

the chances that the particle will pass straight through KamLAND

undetected. Thus, the oscillation

manifests as a "disappearance" or "deficit" of  s. s.

|

|

|

As time goes on, we detect more and more  s. We sort the

particles according to their energy (i.e. their speed), and compare how

many we get at each energy to the number we expected to detect in the

absence of oscillations. The deficit at each energy gives us precise

information on the values of the masses and the mixing parameters. The

picture on the left shows the expected number of s. We sort the

particles according to their energy (i.e. their speed), and compare how

many we get at each energy to the number we expected to detect in the

absence of oscillations. The deficit at each energy gives us precise

information on the values of the masses and the mixing parameters. The

picture on the left shows the expected number of  s we would count as a

function of energy for no oscillations, and also contains several

curves showing what the expected counts would be for different

values of Δm2,

which equals m12 - m22.

Notice how different the oscillation curves are from the no oscillations

curve, and from each other. s we would count as a

function of energy for no oscillations, and also contains several

curves showing what the expected counts would be for different

values of Δm2,

which equals m12 - m22.

Notice how different the oscillation curves are from the no oscillations

curve, and from each other.

|

The main reason we study neutrino oscillations is just to learn more about neutrinos and particle physics. Right now very little is known about the actual values of the three masses. More precise values of neutrino oscillation parameters may help guide theorists in finding new, more complete particle physics theories, such as Grand Unified Theories. Detecting oscillation has ruled out all theories that require neutrinos to be massless.

Neutrino mass and neutrino oscillations play an important role in other scientific areas as well. For example, researchers studying the inner workings of the sun have mounted enormous evidence that neutrino oscillations are the reason why all experiments counting neutrinos from the sun over the past few decades have all reported a large deficit (about half) compared to the number expected from theory. KamLAND stands to be the first experiment to test this hypothesis using antineutrinos created on the earth. For more information on this very interesting research, read any of these non-technical articles on the subject from the webpage of John Bacall, one of the leading researchers in solar neutrino physics.

As mentioned before, detecting neutrino oscillation implies that the particle must have mass. Cosmologists are interested in the role the mass of the neutrino plays in the birth and development of our universe, and its ultimate fate. Depending on how heavy they are, neutrinos could make up a sizeable fraction of the dark matter in our universe.

We hope you agree that neutrinos and neutrino oscillations are quite exciting to study. Please feel free to ask us your questions about neutrino physics. Also take a look at some of our collaborators' pages and some of these resources for the curious.