Detecting Antineutrinos in KamLAND |

|

Detecting Antineutrinos in KamLAND |

|

To detect an antineutrino ( , the

antiparticle of the neutrino), we wait for one to smash

into a proton (p) in our detector. The collision destroys the incident

antineutrino and proton, but creates a positron (e+) and a neutron

(n). As will

be described below, the positron and neutron make two distinct flashes

of light in the detector, which are the "signature" of an antineutrino. , the

antiparticle of the neutrino), we wait for one to smash

into a proton (p) in our detector. The collision destroys the incident

antineutrino and proton, but creates a positron (e+) and a neutron

(n). As will

be described below, the positron and neutron make two distinct flashes

of light in the detector, which are the "signature" of an antineutrino.

|

|

|

As the positron travels through KamLAND's liquid scintillator, it emits light in all directions. The faster it moves, the more light it emits. If you could see it, it would resemble a microscopic shooting star. After moving only a few centimeters, the positron runs into an electron (e-) and annihilates. The scintillation and annihilation occur so quickly that together they look like one brief flash of light. |

| This light is detected by phototubes (short for "Photo-Multiplier Tube" or "PMT") mounted on the inside surface of the steel sphere that holds the liquid scintillator. When light hits the phototube, it makes a small electric pulse, as shown at the right. |  |

| A positron event by itself is not enough to distinguish an antineutrino event. All energetic charged particles -- including electrons, muons, and protons -- create flashes of light in the scintillator. Although we only expect to detect at most two neutrinos per day, KamLAND records about 30 such random flashes every second! |

|

Remember that at the same time the positron was created by the antineutrino-proton collision, a neutron was also created. This neutron bounces around for about 200 microseconds (on average) before it runs into another proton, and the two bind together to become a deuteron atom. In the binding process, another flash of light is released, always with the same brightness. This flash is also detected by the phototubes. |

antineutrino spectrum |

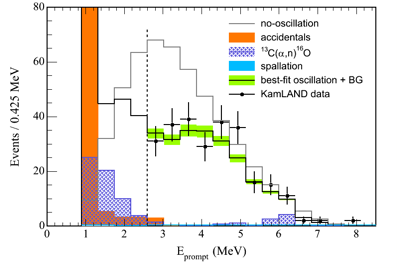

So to summarize, an electron-antineutrino collides with a proton in the liquid scintillator and creates a positron and a neutron. The positron creates a flash of light, the brightness of which determines the energy of the antineutrino. A short time later, the neutron creates another flash of light, which distinguishes the event from the flashes of other particles. The goal in the end is to measure the rate of antineutrinos arriving at KamLAND, and to determine their energy distribution, an example of which is shown on the left. |